Understanding and Managing Chemo-Induced Myelosuppression as an APP

Chemo-induced myelosuppression can affect patients’ ability to do daily tasks, and management varies by patient, treatment regimens, locations, and more.

Chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression (CIM) significantly impacts quality of life for patients with cancer and leads to reactive symptom management in many cases, with management plans dependent on a number of factors, agreed advanced practice providers (APPs) who participated in a Case-Based Roundtable discussion hosted by Oncology Nursing News.

At the event, moderator Chaely Medley, AGNP, of Novant Health Cancer Institute in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, led a discussion with peer APPs on management of CIM with a focus on managing the toxicity in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer.

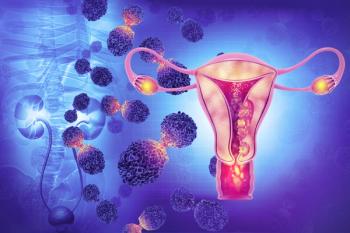

What is chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression?

To start the discussion, attendees responded to a poll prompting them to rate their confidence in managing patients ES-SCLC experiencing CIM on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being “not confident at all” and 5 being “very confident.”

Out of 14 attendees, the majority (85.7%) rated their confidence at 2, or “somewhat confident.” An additional 14.3% reported being very confident here.

“The most important part of learning about how we manage these patients is learning about what exactly is chemo-induced myelosuppression,” said Medley following poll results.

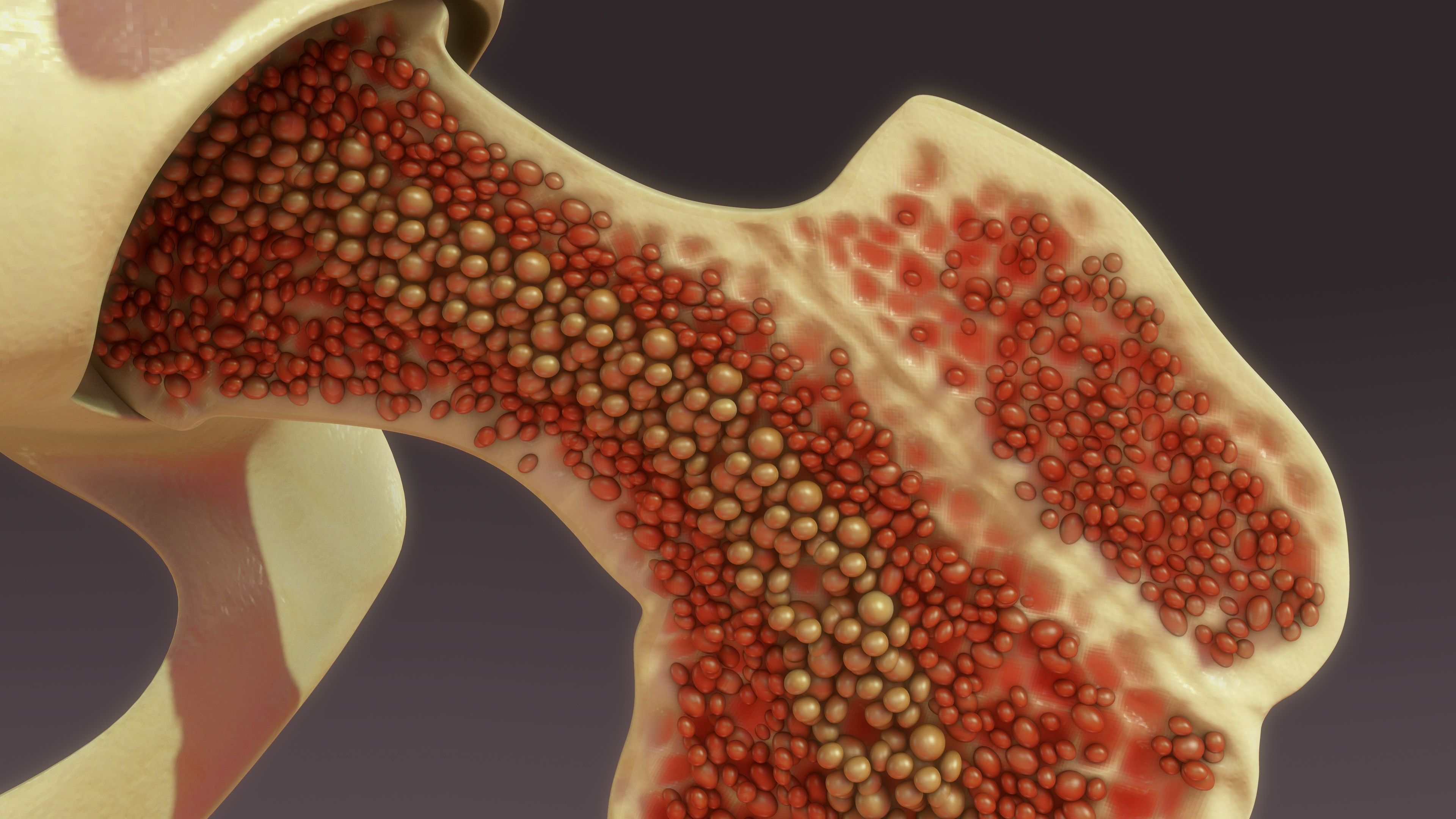

She went on to explain that hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, which produce normal blood cells including red and white blood cells as well as platelets, can be broken down by chemotherapy. The destruction of these cells can lead to neutropenia, anemia, and/or thrombocytopenia as fewer blood cells are produced.

However, reducing, interrupting, or delaying chemotherapy can lead to poorer outcomes for patients with ES-SCLC.

How does CIM affect patients?

A survey of 301 patients with solid tumors and CIM revealed that 88% felt that their quality of life was worsened, and 79% required treatment.

“That number is interesting, because I feel like there are so many patients that come in and they probably could stand to have a blood transfusion, and they say, ‘No, I don't want to do that. I don’t want to spend the time. I don’t want to come back, whatever it is,” remarked Medley. “I think that [number] is probably higher [than 79%], because we have to take into account that patients have a say, and sometimes they don’t want to do what we recommend.”

Additional data revealed that CIM impacted the ability to work for 43% of patients with CIM; moreover, 36% and 24%, respectively, of patients with CIM felt their ability to complete daily tasks within the home and their ability to shower, brush their teeth, or get dressed, was compromised.

“The one that bothers me the most about this is the 24% unable to shower, brush their teeth or dress themselves,” said Medley. “Many people would get to that point and say, ‘I don't want to live anymore. I can't even go to the bathroom by myself.’”

Relationships are also affected by CIM, with 27% and 24%, respectively, finding their relationships with children/extended family and spouses/significant others significantly impacted and 31% feeling their opportunities to socialize were affected.

A large-scale, retrospective study observing over 3000 patients with ES-SCLC in the community setting reflected that regarding grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs), 45% had high-grade neutropenia, 34% had high-grade anemia, and 33% had high-grade thrombocytopenia.

An additional 20%, 23%, 20%, and 15%, respectively, had high grade anemia and neutropenia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, anemia and thrombocytopenia, or all 3, that was grade 3 or higher. More than half of patients had a grade 3 or higher hematologic AE in at least one lineage.

Red blood cell platelet transfusions were required for 10.7% and 2.5% of patients, respectively, with 84% requiring a long-acting G-CSF, which, for most patients (61%), were called for within 3 days of chemotherapy initiation.

Insights From the Front Lines

Medley explained that when she worked at an academic facility, addressing myelosuppression was as simple as adding units of blood to the patient’s infusion line. “I could just tack on 2 units of blood to their treatment, and that was so easy, said Medley.”

Now, in the community setting, if she discovers at an appointment that patients are experiencing these symptoms, treatment is not as accessible.

“It’s a completely different infusion center. It’s a completely different day,” said Medley. “I’m having to decide, am I going to delay you and give you blood or am I going to roll the dice and treat you and hope that they can give you blood the next day or 2?”

Medley emphasized that not only is this an issue of patient safety and experience, but patients will also incur another bill from this treatment.

In a poll of attendees at the discussion, 10 out of 14 reported that anemia affects the most of the 3 major cytopenias. Five participants indicated that anemia was also the hardest cytopenia to treat in clinic, with 4 reporting that the 3 are comparable in terms of management, and 2 respondents each reporting that neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were the most difficult.

One participant explained that part of what makes managing thrombocytopenia difficult is that it may cause more treatment breaks. Patients’ insurance and chair time are also factors that complicate management, said attendees.

Managing CIM

The following strategies are part of a reactive management plan for single-line hematopoietic events:

- Chemotherapy dose reductions or delays, which may limit efficacy

- Hematopoietic growth factor support (lineage-specific and reactive after AE onset)

- Granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSFs), which may cause musculoskeletal pain requiring management through NSAIDs, antihistamines, or opioids

- Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), with or without iron; these are used for anemia and can increase the risk of thromboembolic disease

- Blood transfusions and platelet transfusions; platelet transfusions are a temporary solution, as platelets are limited. Risks of thrombotic events, occult infection, immunosuppression, alloimmunization, and transfusion reactions should be considered.

In discussion, patients added that preventative measures can sometimes be taken before hematologic AE symptoms occur if there is a known high risk with the patient’s regimen.

Newsletter

Knowledge is power. Don’t miss the most recent breakthroughs in cancer care.